Niall Enright was honoured to present at a panel at the Dubai Sustainable Cities Summit on the theme of Behaviour. Fellow panellists were: Sam Adams, Director, U.S. Climate Initiative at World Resources Institute; former Mayor of Portland, Oregon; Romilly Madew, CEO GBC Australia; Dr. Abdulla Al Karam, Chairman of the Board of Directors and Director General of KHDA; Giovanni Schiuma, Deputy Mayor of Matera, European Cultural Capital 2019.

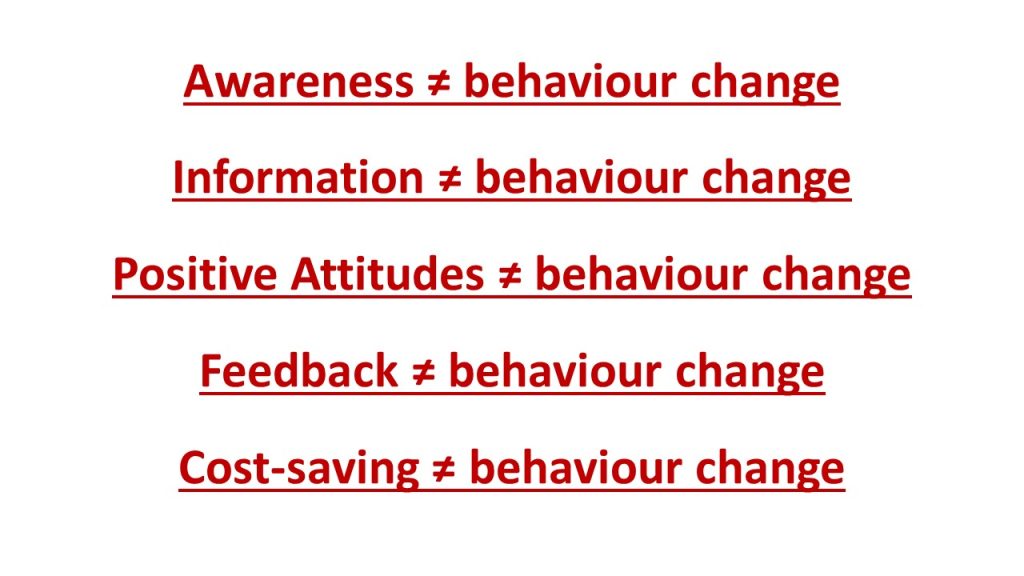

Niall’s introductory comments focused on the need to avoid over-simplification in change programs, emphasized by the “does not equal” symbol “≠”. Below is a complementary paper which places these observations in the context of Dubai’s ambitious energy efficiency programmes:

Thinking of change as a science

In 2004, the Canadian government spent CAN$37m on “The One-ton Challenge” to encourage Canadians to reduce their emissions by one tonne of CO2 each, or 20%. It succeeded in raising awareness of climate issues from around 6% to 51%, but few people changed their behaviour as a result.

Unfortunately, this is just one example of dozens of behaviour change programmes that have disappointed. The landscape of sustainable behaviour change is littered with failure. Contrary to our expectations:

So what does this mean for Dubai, which has great aspirations to become a leader in sustainability?

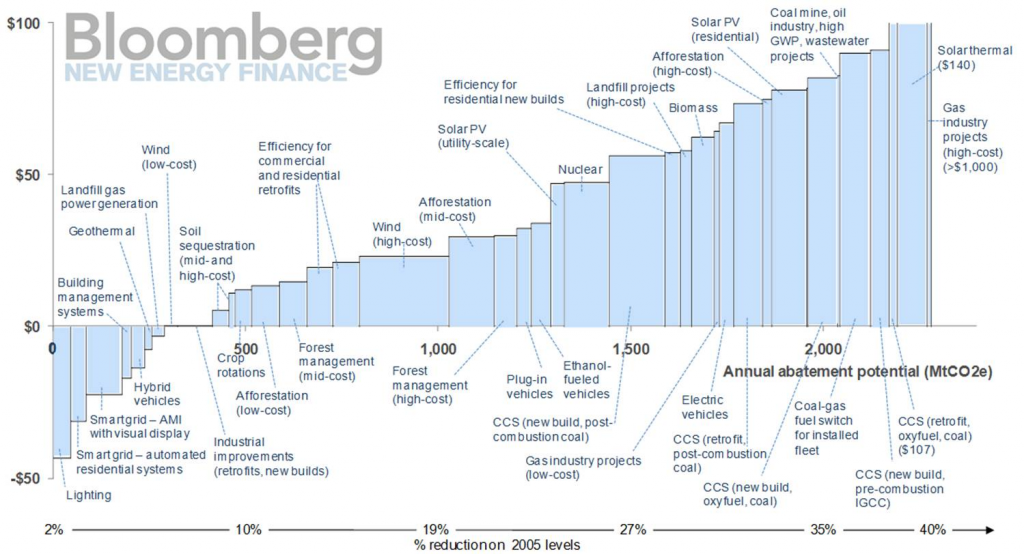

Dubai has set itself the objectives of a 30% reduction in energy use by 2030 and a 40% reduction in water. The eight programmes in the Demand Side Management strategy are clearly carefully considered, focusing primarily on technology upgrades to achieve this demand reduction.

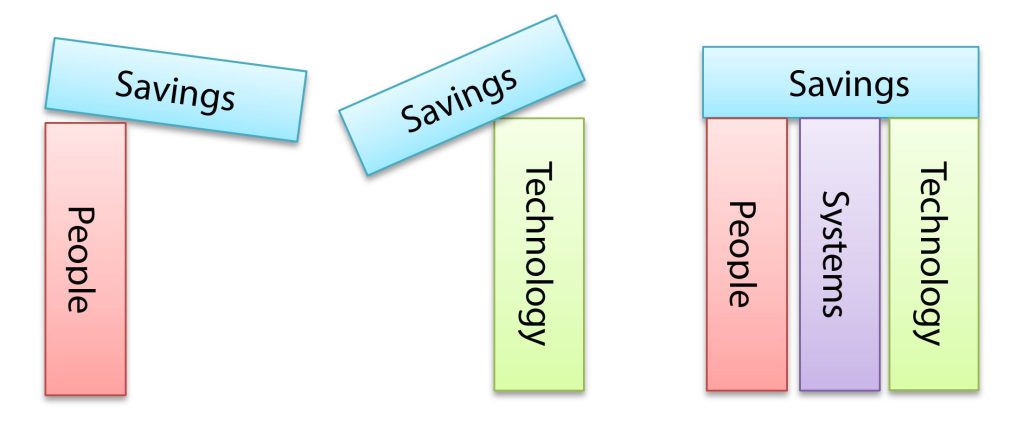

The DSM programme reminds us that cities have three fundamental levers for change: People (their decisions and behaviours), Systems (the norms, incentives, standards, information and feedback that drives behaviour and controls) and Technology (the efficiency of the equipment in delivering the required service).

The illustration above makes two key points. The first we have already touched upon and is shown on the left: changing aspects people’s awareness and motivation alone are not guaranteed to deliver improvement.

The second figure reminds us that technology alone is not a solution. Many technology programmes miss their expected target because people are not properly considered in the project.

It is great to see that the Dubai DSM strategy has public awareness as one of the implementation mechanisms supporting the eight programmes of work. So public engagement, and presumably, behaviour change is built into the strategy. This makes absolute sense. For example, the appliance, labelling scheme and demand-side response DSM programmes depend on people making rational choices.

I note too that over 60% of all building energy use in Dubai is due to cooling. A 2oC increase in the thermostat could achieve 16% reduction in energy consumption. So a good behaviour change programme could deliver a very significant contribution to the overall target, and at comparatively low cost.

Which brings us back to history. As my fellow countryman Winston Churchill, once observed:

“Those that fail to learn from history, are doomed to repeat it.”

The error of history that we need to avoid is a failure to incorporate the lessons from psychology, social sciences and behavioural economics into the design of behaviour programme. The Canadians could have prevented their costly mistake if they had heeded an earlier study that showed that US$200m of expenditure in California had failed to reduce energy use a decade earlier. That study made the recommendation that advertising should not be used alone to drive change.

So what else does the scientific literature tell us?

It tells us that, like information, attitudes have surprisingly little bearing on behaviour, and that advertising simply cannot create new behaviours. Furthermore, there is no “virtuous escalator” of improvement. Asking people to make small changes (such as changing to LED lights) does not lead to bigger changes (such as installing solar PV). If you ask people to do little, you get a programme that achieves little. When people’s motivation to change is financial, then we should not expect to see further environmental behaviours from them.

The literature also tells us what does work. We know that the messages that fail in the mass media can work if delivered through a community context or, better still, face-to-face. If we combine feedback and information we see some effect, and when combined with a goal, even more and when that goal is ambitious there is an even stronger effect and if the goal has been set by the individual it is even more powerful. We know that the effect of feedback increases with frequency and by getting people to measure the improvement for themselves (called “re-materialization” by psychologists).

We know that changing occasional behaviours is easier than changing habitual behaviours. Thus, product labelling is effective because buying a TV or fridge is occasional and so people consider information in making the decision. We have evidence that changing from an A to G rating to an A++ to D rating in the EU rating substantially weakened the desirability of the top rating through psychological effects called “anchoring” and “loss aversion”.

How we frame our request has a much bigger impact that we ever suspected. For example in a large US study, when people were told that their energy consumption was higher than the average they behaved by reducing energy use, but when told that it was lower than average, their response was to increase use. The same study showed that this response could be eliminated by putting a positive message in the form of a simple smiley-face next to the savings information. These effects are due to the way that norms influence choices (the first case is the “descriptive norm” that sets the normal level and the second an “injunctive norm” that reinforces low consumption as socially desirable).

Simply put we need to treat the people aspect of our programme as a science and not an art. Since many aspects of human behaviour are counter-intuitive, the key to success is to design our behaviour change strategies scientifically and test these using the great body of knowledge that exists in the scientific literature.

The energy management system of Peel Land and Property has recently completed certification to the prestigious ISO 50001 standard. As far as we are aware, it is the first major UK property and development organisation to achieve this accolade. Just to give some scale to the scope, the portfolio of assets certified include 1.2m m2 of property, including prestige offices in Liverpool, Manchester and elsewhere in the UK; the MediaCityUK development in Salford, home to the BBC, ITV and dock10 studios; The Lowry and Gloucester Quays Retail Outlets; EventCity, the second largest exhibition space outside of London; Robin Hood Airport Doncaster Sheffield and Durham Tees Valley Airport as well as extensive residential, industrial warehousing and retail park space.

The energy management system of Peel Land and Property has recently completed certification to the prestigious ISO 50001 standard. As far as we are aware, it is the first major UK property and development organisation to achieve this accolade. Just to give some scale to the scope, the portfolio of assets certified include 1.2m m2 of property, including prestige offices in Liverpool, Manchester and elsewhere in the UK; the MediaCityUK development in Salford, home to the BBC, ITV and dock10 studios; The Lowry and Gloucester Quays Retail Outlets; EventCity, the second largest exhibition space outside of London; Robin Hood Airport Doncaster Sheffield and Durham Tees Valley Airport as well as extensive residential, industrial warehousing and retail park space.