Ever wondered why there is such a high level resource waste in our organisations despite study after study showing a vast cash-positive potential across most sectors of our economy? Could this be a reflection of quality of resource efficiency proposals that are reaching senior executives? Are the engineers, consultants, environmental managers or operations staff who are developing these proposals simply not effective in communicating the benefits to decision-makers?

In defence of the proponents of resource efficiency the magnitude of the obstacles to the adoption of resource efficiency are only just now being appreciated. We shall see later in Part 3 “The Barriers to Resource Efficiency”, that the dice are well and truly loaded against resource efficiency right from the start. There are numerous psychological factors, organisational, financial and information issues, which conspire to make the case for resource efficiency much more challenging than it need be.

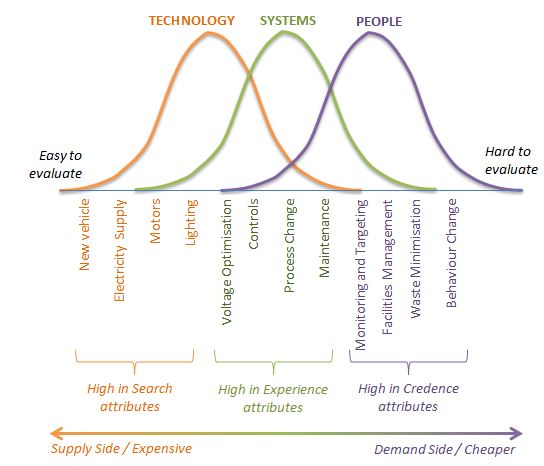

One of these challenges is related to the core nature of a resource efficiency program. Economists talk about anything we buy, whether it is a program – such as our resource efficiency project – or a piece of equipment, as falling into one of three groups. The first group are search goods – items where the buyer, through research, can establish the characteristics or benefits that it will bring prior to purchase – an example of a search good is a new car where trustworthy independent fuel-consumption data is available to inform the choice in advance. The second category is experience goods where the consumer will only really know if the goods have delivered the expected benefits after purchase – for example a second-hand car is an experience good because despite published data being available the owner will only know how efficient this particular used car is after they have brought it and driven it for some time. Finally we have credence goods where there is no way of determining clearly before or after purchase if the goods are delivering the expected benefit and so consumers have to rely on some other form of evaluation to assess their performance – keeping with the cars analogy, an example of a credence good would the repairs that a garage says are needed on your car, which we do not know are required in the first place and which may or may not deliver a benefit. In credence goods the buyer is almost entirely dependent on the seller’s superior expertise and may consequently be cheated – in the early 1990’s 53% of car repairs in the US were found to be unnecessary[ wolinsky1995competition ]. Some credence goods such as medicines or legal services are subject to government regulations so that consumers are protected in the absence of clear (or easily understood) evidence of benefit. These three categories represent a risk spectrum – from the lower risk search goods through to the much higher risk credence goods which are essentially brought “on faith”.

So where does our resource efficiency program fit on this spectrum of risk? Well, while individual items (such as buying a new boiler or a new water treatment plant) can be considered search goods, when we look at a program as a whole then the level of uncertainty about the performance of all the individual technologies combined, variability in the hours of operation, the behavioural response of our staff, as well as the high search costs (costs to research the savings potential in advance), and numerous other variables, means that the program as a whole can be considered as an experience good. That is to say that the decision-maker doesn’t really know what the outcome will be until after they have embarked on the program – the level of certainty in advance is perceived to be low.

In practice the true outcome in many resource efficiency programs are difficult to assess even after implementation, (unless the reader adopts some of the techniques, such as Monitoring and Targeting, M&T, or Measurement and Verification, M&V, set out in this Handbook) simply because of the numerous external factors (such as weather, production volumes and mix, organisational boundary changes, resource costs etc.) that influence resource use and so mask the impact of the changes. In these circumstances resource efficiency can be described as a credence good. In other words the decision-maker may not be confident that they can determine the benefits that it will bring even after the program has been put in place and so will have to make a decision on the basis of other factors, in particular the reputation or expertise of the proponent for the program.

In essence products are easier to evaluate than services. A new motor will have comprehensive manufacturer’s data on operation at different loads and so is easy to evaluate, compared to, say, a behaviour change program asking people to switch off the lights, whose impact is relatively unpredictable. The more our resource efficiency program engages with people, the more likely it is to achieve continuous improvement and to deliver the preferred low cost demand improvements rather than the more expensive supply side changes. However, because people aspects are more difficult to predict, incorporating these into our program has the effect of making the program as a whole more of a credence good and thus more difficult to sell to decision-makers.

Figure 73 Economists can explain the observed bias towards technical fixes for resource efficiency as a consequence of the ease of evaluation or certainty of these solutions in comparison with systems or people based approaches which require a greater “leap of faith”. Unfortunately technology approaches tend to focus on the supply-side whereas demand-reduction improvements tend to be cheaper but more difficult to quantify in advance.

From an economic perspective[ hewett1998achieving ], resource supply and resource efficiency are substitutes for each other – each can be used to meet the organisations needs for goods and services (materials, water, heating, cooling, lighting, etc.). Organisations have a choice between simply purchasing the necessary level of resource (the status quo supply option), or purchasing a new service (the resource efficiency option) which may be cheaper but is, as an experience or credence good, essentially a “leap of faith”. From the decision-maker’s perspective, resource supply is a simple and easily understood product – with suppliers which are long-established and trustworthy, product attributes which are well-known and with an established buying process. Thus the supply option consists of low-risk, search goods whose costs and benefits can be quantified through a standard procurement process. A resource efficiency program, on the other hand, involves a large number of relatively unknown suppliers with technologies that may not be understood or proven. The individual items of equipment that form part of the resource efficiency option may only be procured occasionally so the research costs in quantifying their benefits may be high. Thus the overall certainty of the benefit is considerably lower in the efficiency option than in the supply option and the transaction costs (overheads) are higher. Given these two alternatives it is not surprising that decision-makers often choose “the devil they know” rather than what is perceived as the riskier option of resource efficiency.

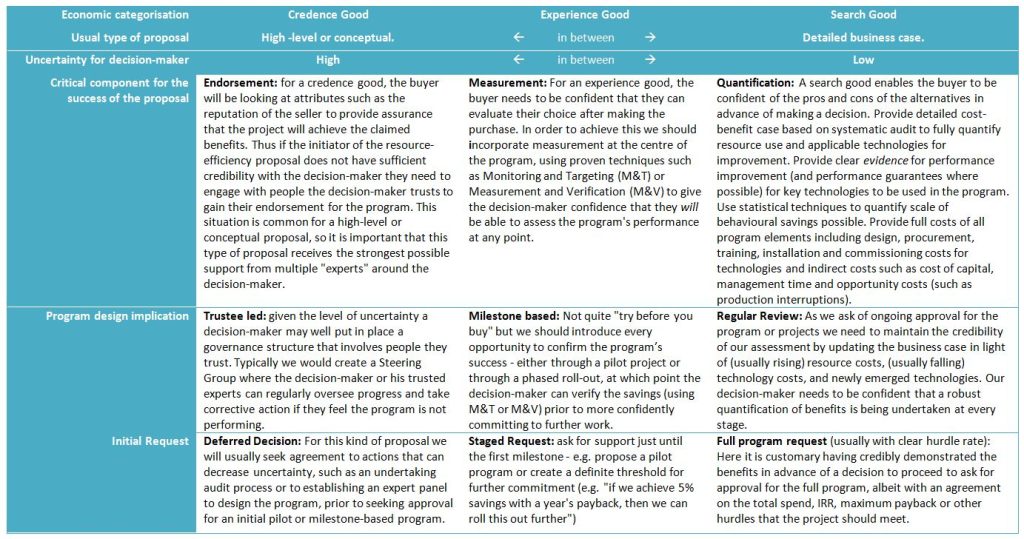

Thus certainty fundamentally influences the nature of the resource efficiency program, as illustrated in Figure 74. In an ideal world we will present the decision-maker with a proposal that fully evidences the outcome to be achieved (i.e. it is a search good) and so it competes on an equal footing with the status quo, the supply option. In practice assembling the necessary evidence for such a business case can be difficult and time-consuming. As a result the initial proposal may well be a high-level conceptual pitch, which is much more of a credence good, which requires the endorsement of a trusted sponsor or expert so that the decision-maker feels justified in giving approval. For a credence approach the request to the decision-maker will usually be not to commit to a full-blown a program but perhaps to approve some further investigation which will enable the proposal originator to return to the decision-maker a second time with a proposal that is less uncertain (much more along the lines of an experience good or a search good). This effort to actively increase the certainty of a proposal at each stage is common in seeking commitments for resource efficiency programs.

If the decision-maker has some initial uncertainty about the outcomes (i.e. they are being asked to commit to an experience good) then we could ask for a pilot to be approved in order to confirm the effectiveness of the process and, using the data gathered during the pilot, we would return for support for expansion of the program, by this time with much high levels of certainty. In effect we are doing what any grocer would do when introducing a product that consumers do not know from previous experience: like a “try before you buy” sample of a new cheese to customers so that they can decide they like it or not.

It is no coincidence that many of the techniques set out in our Method for resource efficiency exist to address the challenges of verifying program outcomes. We shall see, for example, that the continuous measurement of program performance using Monitoring and Targeting eliminates the effect of external factors; while the Opportunities Database provides for constant reassessment of costs and benefits from discrete projects, thus lowering ongoing transaction costs and validating the return on existing investments. Collectively these techniques make our program an experience good rather than a credence good. These techniques guarantee that the outcome of the program will be measured effectively. Thus when we describe the benefits of our resource efficiency program to a decision-maker we may need to communicate some of the techniques that we will use, like measurement, that make it an experience or search good rather than a credence good.

It is important to note that the same considerations of certainty that surround a program approval decision also apply to discrete investments or projects. Where the investment is in a proven technology running for a fixed number of hours, like a variable-speed drive, then this is very much a search good whose benefits can be easily quantified in advance of the decision to proceed. Here the key is to make the comparison with the status quo alternative valid by ensuring that we have presented all costs, not just the equipment but also procurement, commissioning and any other opportunity costs. Where we are considering less tangible projects, such as behaviour change, it is important that we deploy the best possible quantification techniques, such as regression analysis, to make the case for the benefits so that we can increase the certainty in the approver’s mind for these softer projects. These techniques are set out later in this Handbook.

Figure 74 The degree to which a decision-maker is confident of the program outcome determines the design of the program and the initial request for support.

Interesting,

So how to better evaluate the performance of the service? What the sevice providers can do?